MoMu at Future Front Row

April 13, 2024

On the 23rd and 24th of March the screening of the holographic fashion show Future Front Row was presented in Antwerp during the Flanders Technology and Innovation Festival. d_archive was invited by Antwerp’s Mode Museum to work on the digitisation of a 115 year-old ensemble from their Collection and bring it back to life digitally for the show.

The event was a perfect occasion to see this garment moving again on a body outside the safe environment of the Museum’s depot, showing how 3D replicas of archival items can be used to experience fashion in innovative and engaging ways without the risk of damaging precious heritage pieces.

Beyond the three minutes of mesmerising entertainment that visitors have enjoyed during the screening of Future Front Row, the project also holds significant educational value, an essential component of our ongoing collaboration with MoMu.

d_archive team has reconstructed the early 20th century ensemble ensuring its accessibility for future generations by incorporating technical information and patterns derived from the reverse-engineering process. These resources are now freely available on our platform, providing fashion enthusiasts and researchers with invaluable tools for further exploration and study.

You can find the items and the corresponding patterns here: Jacket, Skirt, Jodhpurs and Gaiters.

The Amazone Costume

The chosen outfit is a beige linen horse-riding suit made in 1909 by Hermann Hoffmann, a German tailor specialised in sports and hunting gear. It belonged to a Dutch noblewoman, who we can see wearing it while riding her horse during a trip to Algiers in 1911.

The ensemble is composed of a jacket, a skirt, jodhpurs, gaiters and a bowler hat.

“Riding habits” originated in the 17th century and evolved through decades of fashion into different shapes and forms. In Europe, although the ladies’ side-saddle dated back to the 14th century, women also rode astride until the Victorian era: as horse-riding became a common sport among women of the wealthier classes, the side-saddle became predominant, as riding astride was considered not proper for the gender.

Equestrian wear was usually made of strong fabrics, such as worsted or melton wool, in dark colours so that dirt was less noticeable. In the latter part of the century when travelling to North and East Africa and Western Asia started to become popular within the leisure class, riding habits in light-coloured and lightweight fabrics, such as linen, became part of the travel wardrobe.

The unadorned and utilitarian look of riding habits from the second half of the 19th century is the earliest example of women’s sport apparel, in which comfort and safety were considered in the design of these suits.

Alice M. Hayes, a notorious British horse trainer, in the fifth chapter of her book “The Horsewoman” (1893) describes about appropriate horse riding attire, far from what she defines as “early Victorian atrocities”:

“As safety in the saddle is the first consideration, and as no article of riding dress has proved such a death-trap as the skirt, no lady should ride in one of the old-fashioned, dangerous patterns.”

As well as:

“Whatever shape a lady may select for her riding coat, she should pay particular attention to the fit of the sleeves, which must not in any way hamper the movements of her arms. Before trying it on, its wearer should procure a good pair of riding corsets, which must allow free play to the movements of her hips, and, above all, she must not lace them tightly. Wasp waists have luckily gone out, never, I hope, to return.”

She then describes how she patented “Hayes’ Safety Skirt”, a garment that would allow women to safely ride their horses sideways, while also keeping their legs covered by a skirt when dismounting and walking.

The garment she describes is very similar to the one we can see in this Hoffmann suit: with an asymmetrical construction that allows the skirt to fall nice and flat on the wearer’s legs on the side of the horse, and featuring an elaborate system of buttons and eyelets that will make the apron look like a decorous, full skirt when not riding.

As the cut of these womens’ styles adopted more utilitarian and masculine shapes,commentators on fashion sharply criticised the gender ambiguity of sidesaddle habits, and the French even referred at these suits as “costume amazone”, evoking the -at the time, unladylike and scandalous- mythological image of fierce warriors.

While the riding habit allowed women to engage in physical activity, it did so within the confines of societal expectations. The attire was tailored to maintain modesty, reflecting the Victorian emphasis on propriety even in activities perceived as more adventurous.

As Alison Matthews David highlights1:

“However practical they might be, a woman had to conceal her breeches until the second decade of the twentieth century.”

The Concept

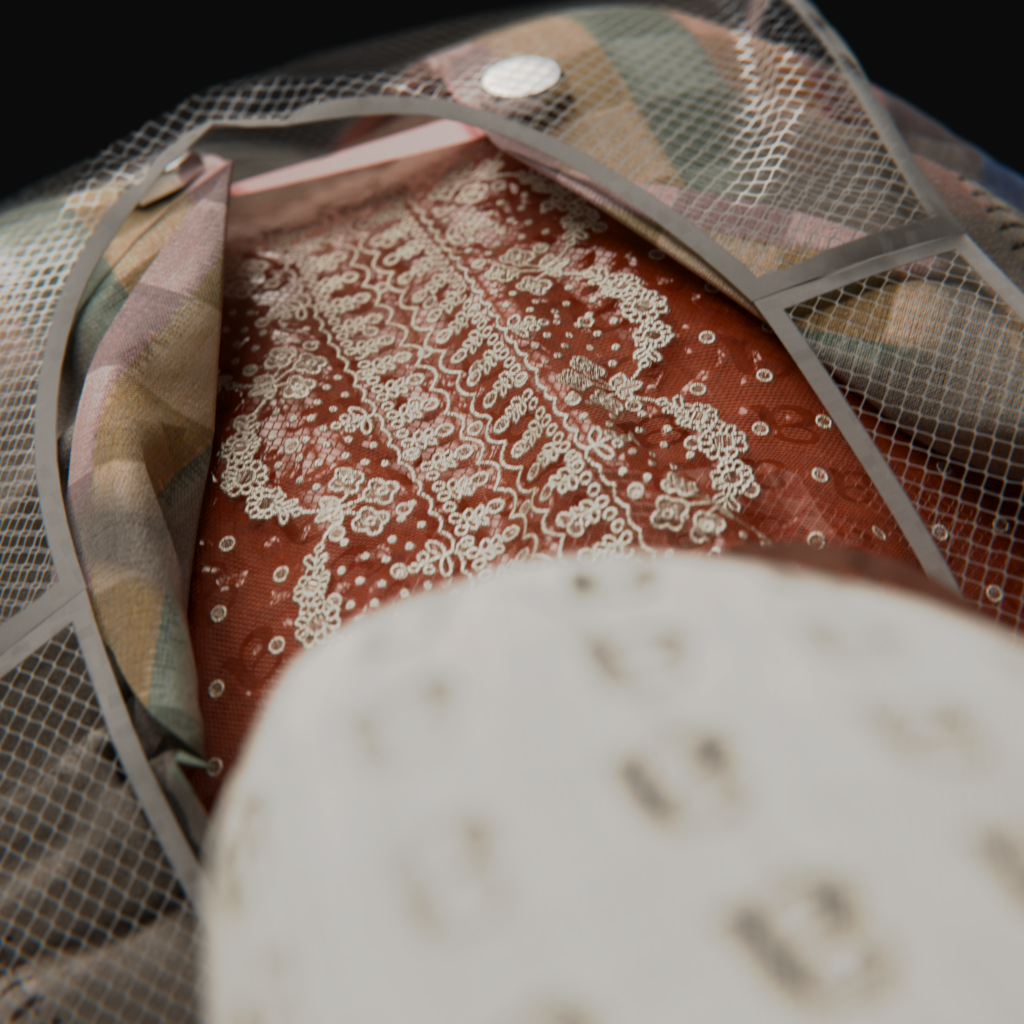

We were once again able to have fun and play around with archival items and reinterpret them. We transformed the pattern of the sober beige linen suit in a ridiculous and unserious ensemble: the jacket becomes a bolero with structured shoulders and flowy orange horse hair trims attached to the sleeves. The gaiters become sharper and stiffer, made of shiny red alligator leather. The skirt turns into a half-apron, keeping the soft pants in sight. The skirt pattern has also been used as a starting point to sew the oversized mesh vest with tactical pockets placed on top of the outfit. Everything refined and dotted by shiny hex-head bolts in place of buttons and rivets.

The look is completed by an edited version of the early 1900s embroidered chemisette from MoMu’s Study Collection.

The concept of the show is about transformation: the flat paper pattern, developed by experienced pattern maker Samira Lafkioui, gets woven into the linen equestrian suit, that then loses its skirt for a public reveal of the hidden breeches that would have been scandalous for the original context of provenance. The piece proceeds to transform into a clown-esque deconstructed interpretation of the original silhouette that uses colourful checked japanese kasuri, organic cotton seersucker and handwoven recycled polyester/cotton fabrics from Antwerp’s own pioneering physical and digital shop, Bakermat.

The contemporary movements have been curated and brought on stage by Sam Aldridge, taken from IOR50 studio’s motion capture archive “Capturing Queer Movement”, a subversive open source tool that aims at destabilising the bleak heteronormative culture that dominates the CGI space.

With the dark and enchanting soundscape produced by Lola Ilegems, the show develops while moving away from a traditional catwalk format into a dramatic and expressive fashion performance.

What’s next

For all the fashion and 3D nerds, we are preparing some behind-the-scenes material to deep dive into the pattern making process, the 3D replica reconstruction and the making of the animation. We will share insights on how traditional and digital craftsmanship can work together to create new accessible means to engage with fashion heritage.

Stay tuned and follow us on social media channels if you’d like to get updates about upcoming events and news. You can find us on Instagram and Linkedin.

If you would like to ask specific questions, don’t be shy, just send an email to contact@darchive.io

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Ann Claes from Maisjen for facilitating the organisation during the FTI event in Antwerp and for working on the network

Special thanks to Mocaplab Paris and Luna Rustarazo for recording the movements that allowed the centenary silhouette to walk on stage.

And finally, we want to, again, thank Kaat, Dieter and Wim from the Mode Museum team for the ongoing support and enthusiasm in working with d_archive.

Notes

1.(From a freely accessible abstract of) Alison Matthews David, “Elegant Amazons: Victorian Riding Habits and the Fashionable Horsewoman”