Maria Sèthe gown for “Fashion&Interiors” exhibition at MoMu

April 05, 2025

In November 2024, while in Antwerp, d_archive team met with curator Romy Cockx, who was working on the upcoming exhibition for MoMu by the title “Fashion and Interiors. A gendered affair”. Romy mentioned how they were planning to include a section regarding the work of cross-disciplinary Belgian artist Henry van de Velde (1863-1957) with special attention to his partner and collaborator, Maria Sèthe, whose contribution to her husband’s creative vision and development was often overlooked.

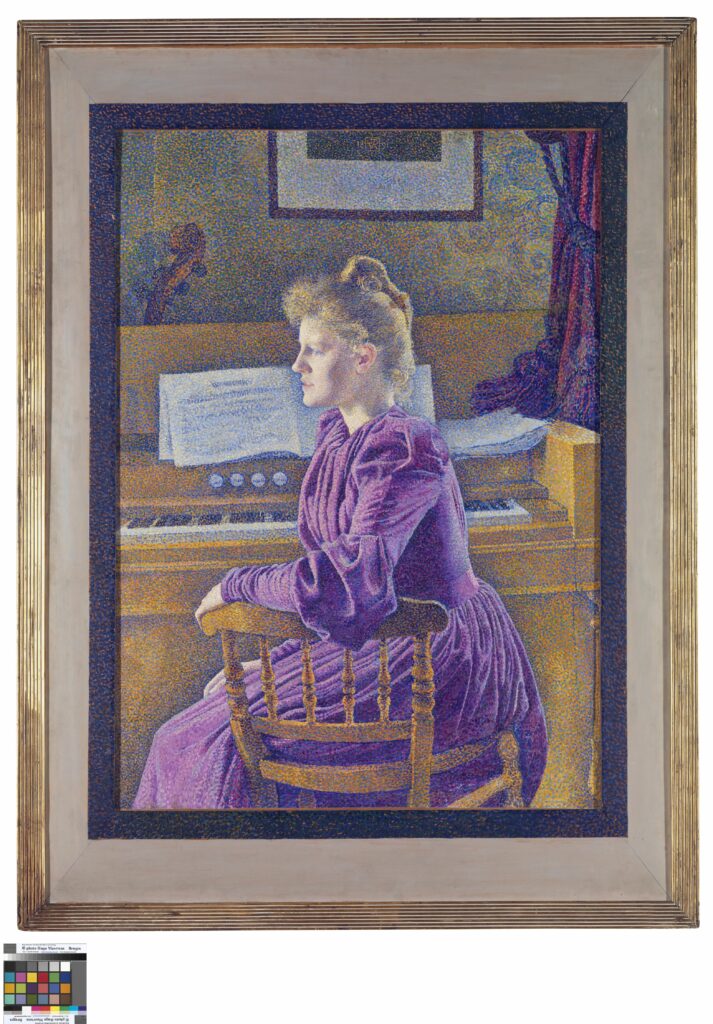

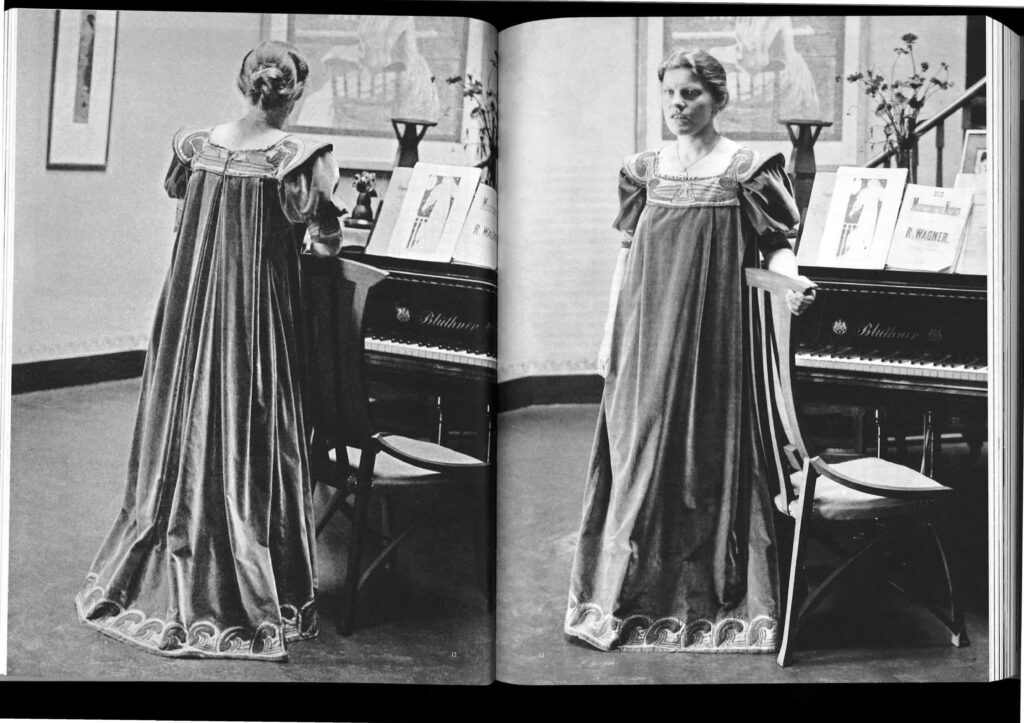

The initial idea for the display was inspired by two photos of Maria posing next to a chair in front of the 1891 portrait “Maria Sèthe at the Harmonium”, wearing a long velvet tea gown with embroidered panels.

The layout for the exhibition aimed to somehow recreate the scene captured in the photo, hence including the very same painting and a chair from Villa Bloemenwerf—respectively part of the collections of the KMSKA – Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp and the Design Museum of Gent— and, ideally, the tea gown.

© Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, artinflanders.be / photo: Hugo Maertens

We would like to share an excerpt from the exhibition book1 to better understand the context of Henry Van de Velde’s work:

[…] She is invariably wearing a dress designed for her by Henry with her input. The idea of designing clothing had stemmed from the total concept that Villa Bloemenwerf represented. According to Van de Velde, the presence of a lady dressed in haute couture in a setting like Villa Bloemenwerf would be sacrilegious. Maria, who had made some of her own clothes before her marriage, helped him execute the designs, which began to appear around 1896. […] ln his memoirs, Van de Velde wrote: Applying the principles of rational conception to ladies’ clothing was part of my aim to give the creation of objects for daily use a new starting point […].

Some of the clothing designs were probably intended for Maria’s pregnancies. She bore seven children between 1895 and 1904 and so for a long period wore comfortable,loose dresses without a corset.

Based on the idea that’the dress is dictated by where it is to be worn’, a view Van de Velde expounded in his 1902 article ‘Das neue Kunst-Prinzip in der modernen Frauen-Kleidung’ (‘The new art principle in modern women’s clothing’), Maria’s wardrobe included garden dresses, reception dresses for receiving guests at home, walking costumes for outdoors and evening gowns. Most of the house dresses were made in softly draping velvet embellished with embroidery on the cuffs, the edge of the skirt, the chest and shoulders. He advocated the ‘accentuation of the visible seams and abstract ornamentation that ’emphasises the constructive cut of the dress’ rather than the outmoded naturalistic adornments that serve no purpose.

This discourse is clearly an extension of his view of furniture design and is visualised in the Villa Bloemenwerf photographs. The line of the embroidery is in tune with the interior of the home, and the photographs of Maria posing next to the furniture emphasise this visual unity.

As Van de Velde explains, the design of the garments was an integral part of his creative vision. Unfortunately the tea gown no longer exists; the only surviving parts are the four embroidered panels for the collar, bottom hem and two cuffs, currently owned by the Museum für Gestaltung in Zürich. This challenge marked the start of a discussion with Romy about the possibility of including a 3D replica of the gown in the exhibition to complete the display.

Scan from: Romy Cockx, Fashion & Interiors. A Gendered Affair, 2025. Page 68-69

We decided to work on a video that would be projected on the wall next to the painting, ensuring that it wouldn’t overwhelm the portrait nor spill over it, as requested by the curator. To maintain this balance, Romy suggested the looping video to be interrupted between cycles.

Since we intended to evoke a homely scene from Villa Bloemenwerf, we thought it appropriate to show the movement of the dress on an animated avatar silhouette—inviting visitors to imagine Maria inhabiting the space.

A dark silhouette, chosen to resemble Maria’s appearance just enough to wear the dress convincingly, but stylised with a mannequin-like neutrality to avoid becoming the focal point, walks into the display “room” from an imaginary door on the viewer’s right. After taking a couple of steps, she stops at a respectful distance from the portrait and idles for a few seconds, gesturing casually and perhaps glancing at her own reflection, before exiting the room.

Through this approach, we were able to speculatively explore the movement of a dress for which no video documentation exists.

Photo of a visitor looking at the installation from the exhibition “Fashion&Interiors. A Gendered Affar” at MoMu, d_archive 2025

The reconstruction process began with Curator Romy Cockx and Textile Conservator and Restaurator Kim Verkens visiting Kunstmuseen Krefeld to study the 1983 replica made by Atelier Jutta Papernberg-Steenbock, based on a then-available pattern.

Kim studied and lifted the pattern from the replica dress and worked on its digitisation with Stijn Van den Bulck – MoMu’s in-house pattern maker. Stijn prepared a 3D prototype of the dress, which was then handed over to the d_archive team for detailing, texturing and fabric simulation.

Working and exchanging feedback remotely between Antwerp and Melbourne, the team adjusted the shape, volume and fit of the dress—as well as the shape and proportions of the avatar representing Maria’s body—until a satisfactory plausible outcome was achieved. Meanwhile, Romy received high-quality photos of all embroidered panels from the Museum für Gestaltung in Zürich, which allowed the team to refine the cut of the neckline and use the photos to recreate detailed 3D textures for all embroideries.

The final 3D replica presents a floor-length gown made of soft, mid-weight dark brown velvet, featuring six big knife pleats in the front and eight at the back, stitched beneath the decorated panel on the chest, and draped softly along the length of the dress to create a roomy straight silhouette. The wide bottom hem, extending into a small train at the back, is also decorated with an embroidered panel. The puffed short sleeves, finished with embroidered cuffs, sit just above the elbow. We assumed the dress may have had a lined bodice for structure, while the skirt was likely unlined.

Renders of the dress, d_archive 2025

Screencapture of the animation work in progress, d_archive 2025

After several hours spent preparing the animation and lighting for rendering, the video was submitted to the museum a few weeks ahead of the exhibition opening, to ensure the projection setup functioned as intended in the display space.

On the day of the inauguration, the team noticed something new in a photo published in the exhibition book:

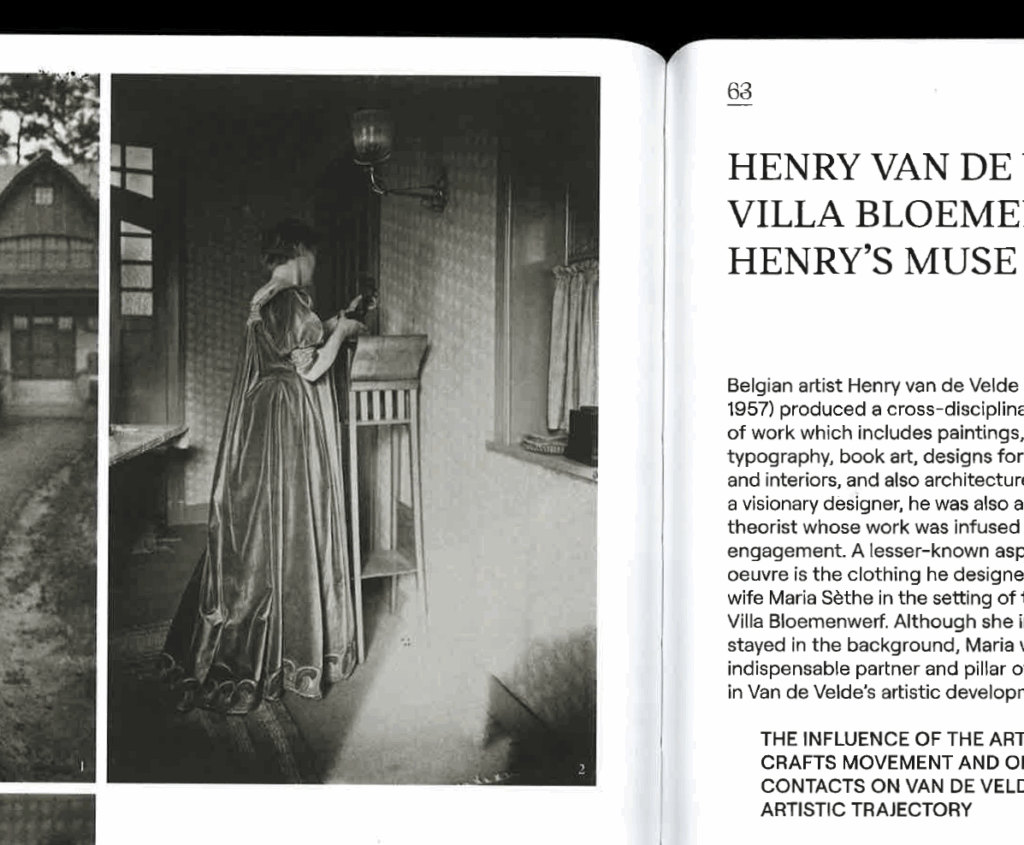

Scan from: Romy Cockx, Fashion & Interiors. A Gendered Affair, 2025. Page 62-63

In this newly surfaced photo of Maria wearing the brown tea gown, a detail becomes apparent thanks to the brighter lighting condition in which it was taken: a tailoring detail on the back of the hip, that was not visible in the previous references used to create the replica.

We assume that whoever prepared the pattern and physical replica from 1983 also did not notice this detail, as the material studied by Romy and Kim at Krefeld Museum did not include any darts or seams in the back panels.

This unexpected discovery prompted a reflection on the flexibility and responsiveness of digital restoration. Unlike physical reconstructions, the digital replica can be revisited and updated with relative ease as new information or references come to light. In this case, the tailoring detail at the back of the hip—absent in the materials used for the 1983 replica—will now be integrated into a revised version of the 3D gown, which will be openly shared with the public once the dress will enter the Public Domain, in 2026. Such an approach offers a compelling model for working with historical garments that are either too fragile, incomplete, or entirely lost.

The use of speculative digital techniques does not aim to replace physical artefacts or traditional conservation methods. Rather, it opens new avenues for engaging with heritage objects by creating research-informed visualisations that invite both critical analysis and imagination. The process of digitally reconstructing the tea gown allowed us to explore not only the materiality and movement of the garment, but also the intimate context in which it was worn—reframing Maria Sèthe not simply as a muse, but as an active participant in a shared creative vision.

As further documentation may emerge the 3D model can evolve accordingly. This capacity for ongoing revision not only mirrors the iterative nature of historical research, but also foregrounds the idea that heritage is not fixed in time. Through digital methods, we are afforded a space where absence can be addressed with sensitivity, and where speculation, grounded in evidence, becomes a tool for both storytelling and preservation.

1. Werner Adriaenssens, ‘Henry van de Velde’s metamorphosis: Villa Bloemenwerf and the role of Henry’s muse Maria Sèthe‘, in: Romy Cockx, Fashion & Interiors. A Gendered Affair, 2025.