The Bee by Walter van Beirendonck at Museum Boijmans van Beuningen

July 19, 2025

In January 2024 we met Gianni Antonia, [now former] Curator of Education at Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam and fellow digital fashion professional. After a few conversations and some brainstorming, he brought forward a 3D project proposal that was approved by the Museum.

We were stoked when d_archive was commissioned to create a 3D replica of a Walter Van Beirendonck silhouette.

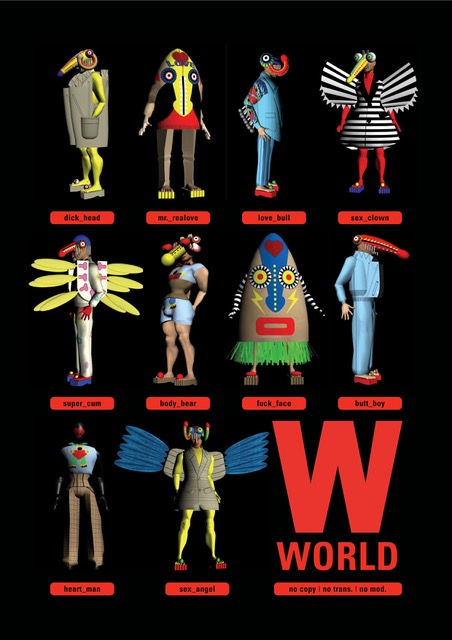

The Bee is an ensemble designed by the Belgian fashion designer in 2007 for his spring summer 2008 collection “Sex Clowns”.

A blurry photo from the 2007 collection showcase in Paris

The Bee at Boijmans’ exhibition “The Art of Fashion: Installing Allusions” (2009)

Original digital illustration of the collection.

Walter van Beirendonck’s sketch of The Bee

It features a full-body red latex suit, including feet, hands and head coverage. The linen/cotton jacket has thick off-white canvas stripes applied on top, two decorative flaps without an actual pocket underneath. The broad shoulder pieces are heavily fused and supported by (metal?) wiring covered with the same black fabric of the main body.

The preservation of the latex suit is problematic: it discolours due to UV light sensitivity, and cracks appear due to the high tension to which it is subject when wearing it on a mannequin. Over fifteen years, three suits have deteriorated. The latest suit was made directly on the mannequin and it is meant to never be taken off it, but the material remains fragile despite being subject to less tension, meaning that The Bee can only be displayed for very short periods of time, if at all.

Gloves and hood one of the old damaged latex suits.

Due to these conservation challenges and very limited possibility to display the piece, the Museum commissioned us a 3D replica that could be used in lieu of the original outfit, so that visitors could still enjoy the piece and interact with it differently. The idea was to showcase the digital piece on two big touchscreens located near the Museum’s Depot, where the restoration department is located.

The new latex suit assembled on the mannequin.

The jacket, sandals and headpiece being prepared for photogrammetry.

The whole process started, as usual, with the reverse-engineering process, although with some limitations due to the conservation state of the piece: the garments could not be taken off the mannequin they are stored on, and the viewing time was limited to one hour per visit, to make sure the latex suit wouldn’t get exposed to lighting for extended periods. Our team had to visit the Depot twice, with appointments one month apart from each other, to suit these requirements.

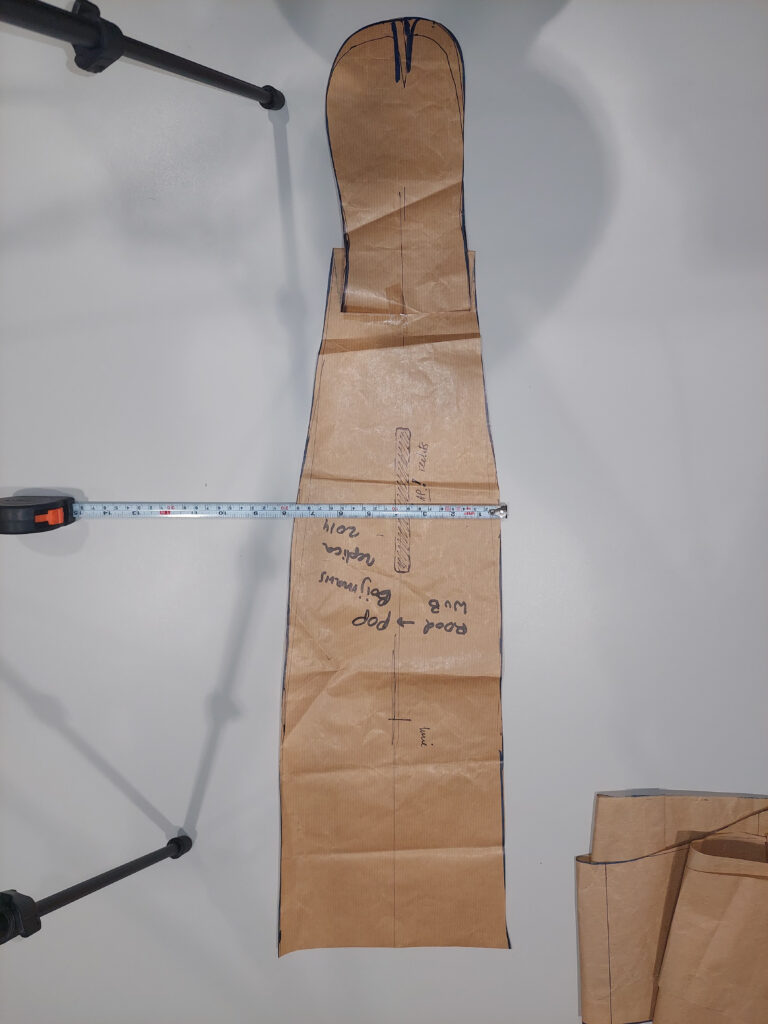

Measuring a garment which is not lying on a flat surface is quite challenging, but not impossible. It worked well for the dress-jacket, also thanks to the quite stiff material it is made of. It would be unthinkable to measure a latex piece displayed on a mannequin though. Luckily, we were able to meet with Linda van Wel, the latex designer that has been working with Van Beirendonck’s brand for a long time, and that was the author of the original suit. Linda was in fact preparing the fourth suit for the Museum ensemble, to replace an old and brittle one. She was happy to share her patterns with us so that we could recreate an accurate 3D replica, and in the lovely and insightful conversation we had, she gave us instructions on how to assemble the latex, which needs to be glued together rather than being sewn.

Measuring the jacket to reverse-engineer its pattern.

Digitisation of Linda’s pattern for the latex suit.

The digitised jacket.

The digitised latex suit.

Since our time with the ensemble was limited, we decided to prepare a rough photogrammetry scan of the entire piece, so that we could use the resulting geometry as a reference for proportions and volumes.

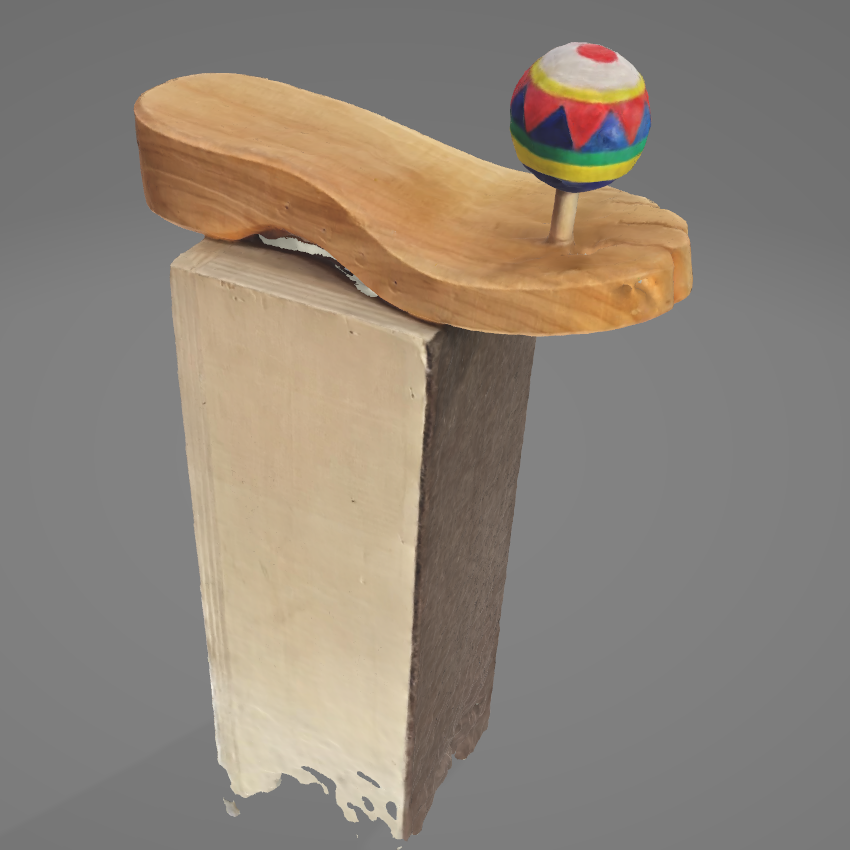

Photogrammetry was also used to scan the headpiece and sandals, which were then reconstructed and textured manually, trying to replicate the hand-painted paper mache details.

The raw results of photogrammetry scanning.

The finalised 3D replica of the headpiece and sandals

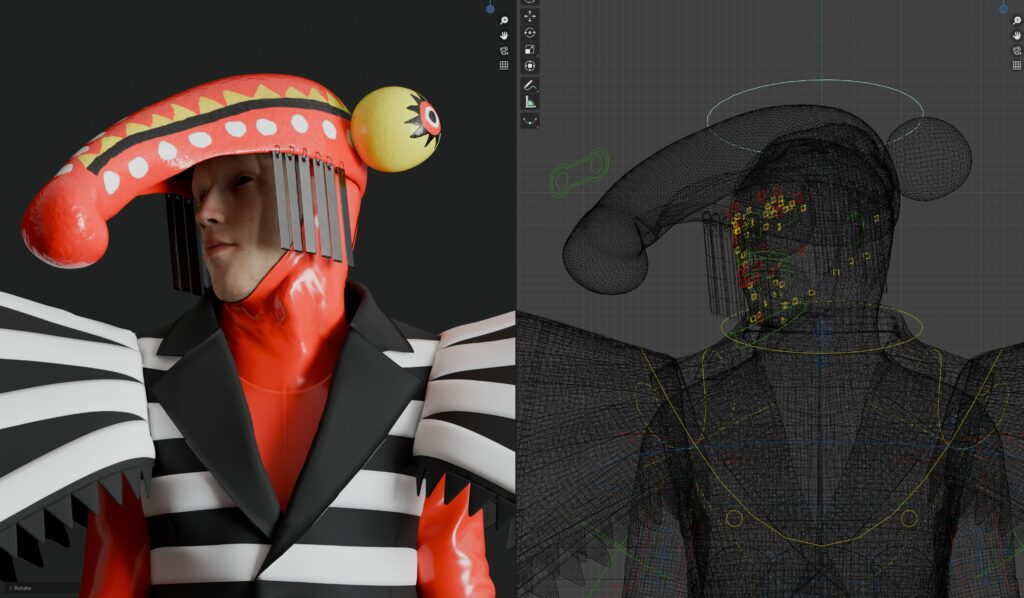

Once the outfit was completed with all its textures and details, as well as a custom shaped avatar to fit the suit, we validated it with the Boijmans Museum team, and moved on to optimising the 3D model to make it suitable for web view.

This is a necessary step when working with most online 3D viewers, as the original model would be too heavy (both in terms of geometry and textures) to properly load and make sure the interactive viewer works smoothly. Through the joys of retopology (our CGI friends will catch the sarcasm here) we were able to find a fine balance between accuracy and efficiency, making sure that the 3D model would still clearly show all the details, while also being much lighter and suitable for its purpose.

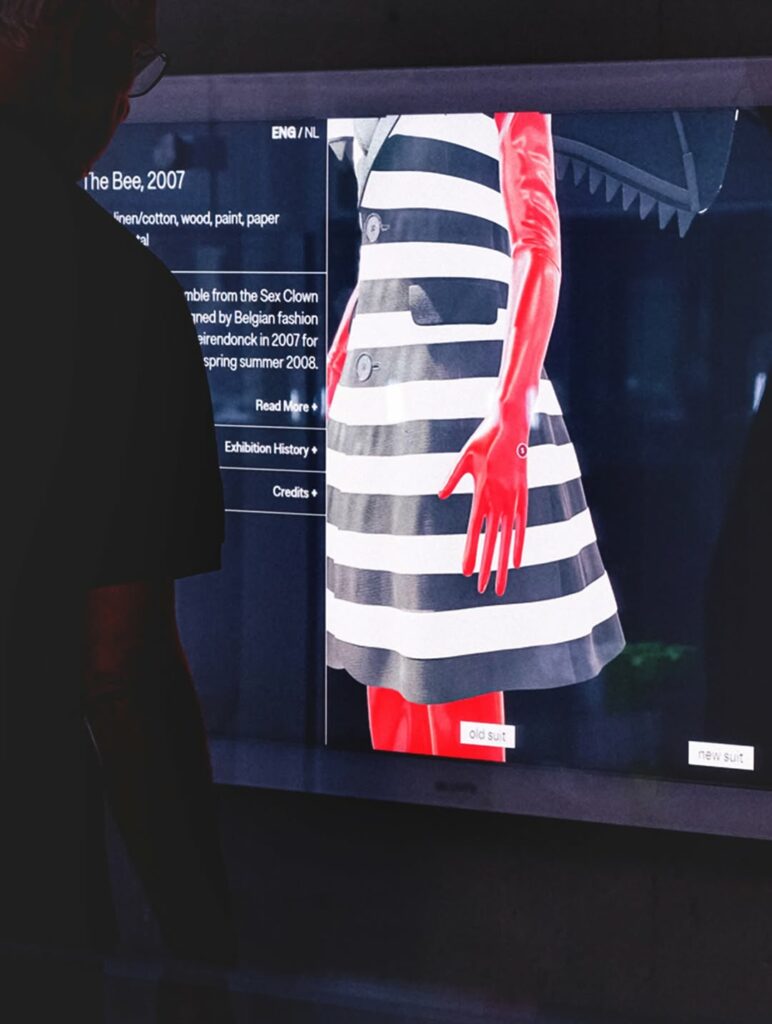

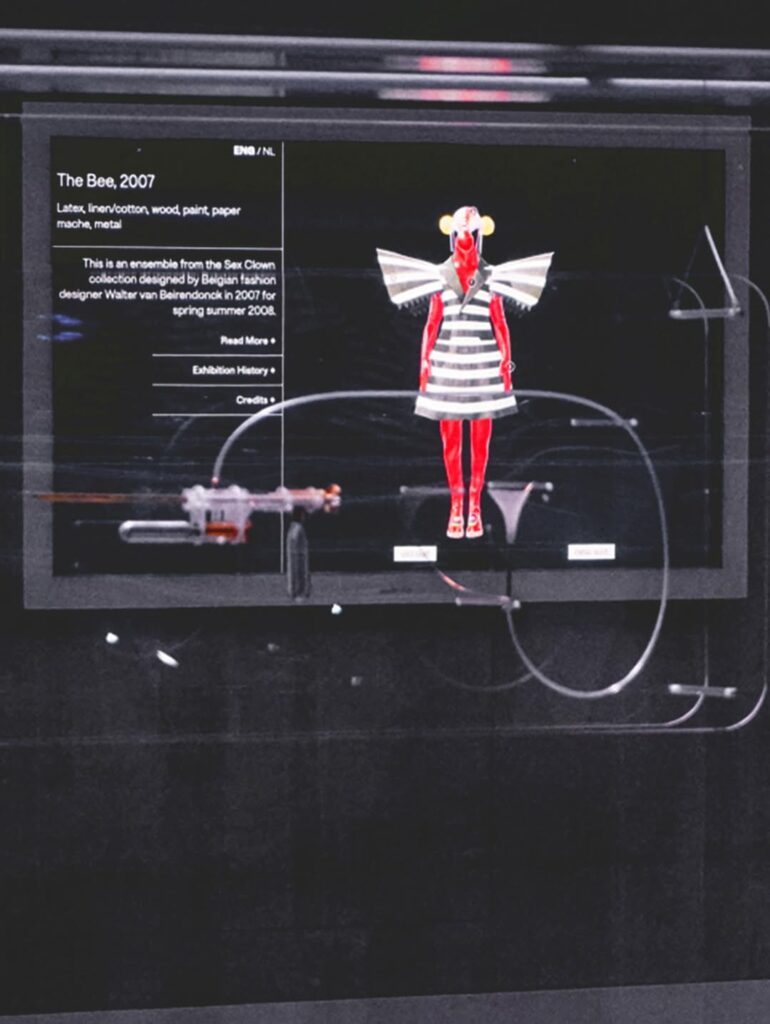

The resulting model was then uploaded to Boijmans Sketchfab profile, and embedded into a custom layout webpage that would become the interface for visitors. Here you can see the final result showing the interactive 3D model alongside information about the silhouette and its exhibition history, available both in Dutch and English.

A screen capture of the final interactive 3D viewer.

Museum visitors are able to click on trigger points that provide more information on the garments and accessories, toggle the texture of the latex suit to see the difference between the dry and brittle material compared to the new one, and rotate and zoom on the piece.

The 3D viewer installed on a touchscreen at Boijmans van Beuningen’s Depot.

Does this replace the experience of seeing the original ensemble? Certainly not.

Annemartine van Kesteren, Senior Curator of Contemporary Design at Boijmans, told us that digitisation of heritage should always be pursued to not only allow more people to experience a piece that they wouldn’t otherwise be able to, but most importantly to also offer new ways of experiencing it that would not otherwise be possible with a physical display (most of all with one that has such strict conservation protocols). Solely offering extended virtual access might alienate visitors from the actual connection with the original object, which is clearly the opposite of any museum purpose. However, giving visitors a chance to see the object under a new light, thanks to its digitisation in this case, might inspire new ways of relating to that same object. And we surely agree with her.

In the case of The Bee, the interactive viewer offers a chance to see close-ups of the garments, to compare the worn out latex with a new shiny material, as well as giving the option to peek under the jacket to see the lining and the multiple layers of tulle that help maintain the volume of the lower part, as well as the boning structure that supports the shoulderpieces.

Van Kesteren also highlighted how movement is a fundamental aspect of fashion design, which unfortunately museums do not really get a chance to integrate in their displays.

The 3D replica that now exists in the digital domain could be animated to show the Van Beirendonck ensemble moving again, without any risk for the physical counterpart (here we joked about the infamous Marilyn Monroe’s dress apparition at a Met Gala…).

She concluded by adding how all the material we collected and produced in the process – dozens of photos and measurements resulting in a cutting pattern and the finalised 3D model – could support the conservation department staff to better understand the piece and aid its restoration if needed.

And if the owner of the Intellectual Property, Walter Van Beirendonck in this case, would be willing to share part of this technical material, it could be used for educational purposes by design schools and fashion nerds (like us!).

Finally, to communicate the project, we decided to give the storytelling a more poetic angle, to avoid falling into a merely technical showcase which wouldn’t do justice to the piece.

The video presents the silhouette in an enigmatic and almost otherworldly way – as if arriving from another planet or dimension. Viewers, unsure of what they are seeing, can only grasp it through its formal qualities: shapes, contours, colours and textures. Metallic plates jingle in the wind, creating a bright clinking sound; bold black-and-white stripes contrast with the saturated, glossy red latex; a textured, multicoloured headpiece crowns the silhouette.

The sound design evokes a living, breathing natural world. Bells, wind, and the hum of bees guide the audience into a ritual of observation – minimal melody, but rich atmosphere. It invites a meditative focus on the garment’s materiality and its evolution over time, marked by the latex’s gradual transformation, behaving almost like an organic skin.

We would like to once again thank Gianni Antonia for instigating this project, as well as Annemartine van Kesteren and all the other Boijmans van Beuningen Museum staff that supported us in its development.

We are grateful to Linda van Wel willingness to share her patterns with us, alongside lovely chats and interesting backstage stories.

We were absolutely flattered to hear that both Walter Van Beirendonck and Stephen Jones appreciated our work, and that they decided to repost it on their socials.